Ria Gruss

Ria Gruss was born in Vienna, Austria, on August 18, 1932, to Athol and Gisele Wohl. She and her younger brother, Stefan, spent their early years in the city’s upscale third district, near the Belvedere Palace, where they lived in a private, three-floor house and identified as secular Jews. Ria’s father was a prominent banker and industrialist in Vienna and Kraków, Poland. Her parents divided their time between those cities while she and her brother were mostly cared for by a governess in Vienna.

Ria’s parents were in Poland when the Germans annexed Austria in March 1938. Ria and her brother were smuggled out of Vienna and reunited with their parents by Oswild Landau, the son of Athol’s partner in Switzerland, who had a Swiss passport. This was the first of many moves that she and her family took over the next few years to escape the Germans. In Kraków, the Wohls lived in a large apartment above the family’s bank, located at the corner of Sarego and Gertrudy streets, near the Planty Park.

There, Ria regularly saw her grandparents and met some of her aunts, uncles and cousins for the first time. A few days after Germany invaded Poland, on September 1, 1939, the extended family split into two cars to evacuate. They headed east to a house belonging to the family of a new Polish Jewish governess they had hired. After just a few days there, bombing sent the family moving east again.

They drove to a town called Zwatruf, where they stayed in the apartment of a Jewish acquaintance while planning to cross the border to Romania. Her father wanted to stay a few days for Rosh Hashanah; her uncle felt they should leave immediately. They stayed and then her father had a gallbladder attack so their departure was further delayed. They moved to Kolomyia, which was near the border, where they stayed in slightly more comfortable conditions. At that point, the borders were closed, the Russians had occupied eastern Poland and the Germans had occupied western Poland. For the first time, Ria attended school for three months.

There were guides who could be hired to cross the border but they couldn’t take too many people at the same time. So in November or December of 1939, Ria’s father and brother, along with her uncle, crossed the border. Ria and her mother were to follow a few days later but the next day they learned that the men had been captured. Ria’s mother went to plead with the Russian authorities at the local jail. She succeeded in bringing her son back home but had no contact with her husband. So she decided to join her own family -- her parents, older sister, brother, sister in law and their children -- in Zwatruf. Ria's mother’s brother, Joseph Schtiglietz, managed to get a job in Lwów, and would visit from time to time. His income, connections and resourcefulness proved life-saving to Ria and her family throughout the war.

Life was peaceful for a short time until the Russians came and loaded Ria and her family onto trucks, transported them to trains and deported them. There were approximately 70 people packed into each cattle car on a trip that lasted roughly six weeks, travelling far eastward until Kurskaya Oblast, near Yakutsk. Her brother and cousin contracted scarlet fever and somehow survived despite the unsanitary conditions and minimal food rations.

The journey ended in August 1940 at a settlement by the Taiga forests in Siberia, where the deportees were assigned barracks and registered for manual labor and communist school. They slept on one long bunk made of wood right above the floor and were given identification cards for food rations. They endured months of harsh winter and endless snow when in April 1941, Ria’s mother was summoned by the Russian officers at the settlement and told that she and her two children could return to Poland. After 11 days, they arrived in Lwów, where her uncle was waiting for them on the platform. It was a joyous reunion, even more so when they found out that Ria's father was alive and they were reunited with him after a 10-minute drive.

He had been moved to 11 different jails in the 16 months that passed but was freed by arranging for a relative in New York to get the Bolivian consulate in Zurich, Switzerland, to issue them Bolivian passports. The papers arrived when he was in his last prison, La Lubyanka, but he didn’t want to leave before finding out what had happened to his family. It took three months to locate them.

The family was all set to leave for Bolivia via Japan on June 24, 1941 but the plan was foiled when the Germans invaded Russia on June 22nd. Although the ghetto in Lwów was established right away, Ria’s family was spared that fate because of their Bolivian passports. After two or three months of staying indoors all day, her parents sent her and her brother to the country to stay with the family of their chauffeur’s wife’s because they thought that would be safer. Her parents were subsequently hidden by a German colleague in his office, while the children lived with a farmer, his wife and their teenage daughter.

One day, in August, the farmer took Ria and her brother to an estate owned by a German who was going to help them and their parents illegally cross the border to Hungary. They had to wade through the strong current of a river on the border of Poland, Germany and Hungary, and feared they would be turned in, but they made it safely to Munkács, the nearest metropolis. Hungary had not yet been occupied so the Jews there were living a relatively normal life.

A non-Jewish woman in the square ended up taking them to the outskirts of town to stay in her barn. She gave them food and shelter while her father met up with her uncle, who had illegally crossed into Hungary before them and arranged false papers to pretend they were Christian Poles. From then on, Ria was told to say that her name was Maria Wolinsky. The family stayed in a pensione on the outskirts of Budapest, and for the first time in a while, had comfortable lodging and plenty of food.

Soon after, though, the family was arrested and taken to a detention camp in the center of Budapest. Although they were released, they feared that authorities would discover their papers were fake and send them back to Poland. Also, there was now a tightening of rules against Polish non-Jews as well. So they rented a villa in Leányfalu, which was about an hour from Budapest by train and where a concentration of Polish refugees lived.

The family went to church every Sunday and hired a Polish-speaking nanny to teach the children proper Polish so that they would not be discovered. After the German invasion of Hungary, in March 1944, things became more dangerous. The Germans set up a desk in a house and ordered everyone to register. Men and women were separated for inspection and the husband of the woman who cared for the children, Helena Rochinska, went in place of Ria’s father because his Jewish identity might be discovered if they saw his circumcision. After that, the family made plans to illegally cross the border to Romania, feeling it was no longer safe in Hungary.

They went to the property of an aristocrat in Szeged, who often held parties on his estate, which was the pretense for so many people passing through. They stayed one day and were going to cross the border at night but the party before them was caught and revealed their address. They were arrested and taken to the local jail. They stayed there for six days while Ria’s maternal uncle went to the committee in charge of Polish refugees in Hungary and arranged to have them released to a local Hungarian lawyer.

Right after their release, Ria’s father had another gall bladder attack and the lawyer arranged for him to be admitted to a convent hospital. The children lived with a lady friend of their uncle in Budapest while their mother stayed with their father at the hospital. They could not go outside at all until their uncle moved them to the lodging of a caretaker and his wife on a nearby villa of a Jewish antique dealer.

Ria’s parents were liberated in the hospital but the siege of Budapest by Soviet forces lasted 50 days. As the fighting advanced, Ria’s uncle moved her and her brother to the cellar of the villa, which had been abandoned by that point. It was freezing cold and there was very little to eat so he quickly decided they were going to try to cross the Danube and join Ria’s parents. There was snow on the ground and dead horses and bodies everywhere, and they had to traverse from leaking boat to boat across the pontoon bridge set up to cross the river, but they persevered. When they found Ria’s parents, they immediately left together to a place in southern Hungary called Makó. Ria’s uncle learned that his family had gone from Siberia to Palestine so he left to join them but her family stayed on a farm in Mako for a little more than a month.

Around March they moved back to Vienna, where they stayed in the family’s townhouse from before the war. Then her parents went to Poland and left the children in Vienna while trying to arrange emigration to Brazil. The children joined them there in June, when they had secured visas. In July, they took a train from Kraków to Warsaw and then from Warsaw to Stockholm in Sweden, where they stayed for three months. They finally arrived in Brazil in October 1946, during the heat of summer there, after a month-long four journey by freighter.

Because of her limited formal education, Ria, then 14 years old, was going to be placed in sixth grade. Instead, she studied all summer for the entrance exam to the American School, where she started ninth grade in March. Since she didn’t attend a Brazilian school, she could not attend university there so, after graduation, at the age of 18, she traveled to New York to attend secretarial school and then New York University.

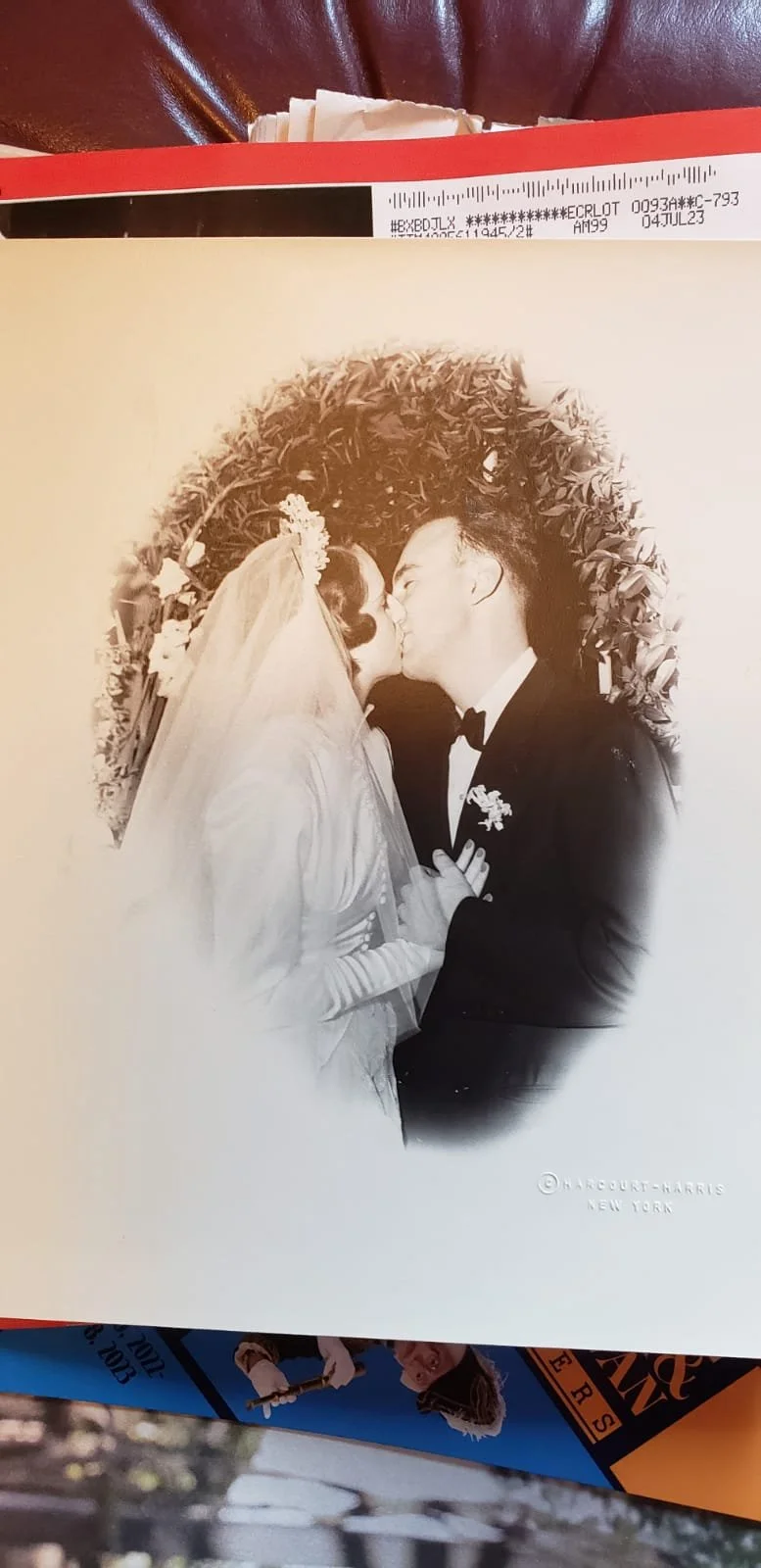

She met her husband, Mike, when her father in law, Oskar Gruss, who had been an associate of her father’s before the war, heard she was alone in New York and invited her to join them for dinner. They were married in 1952 and had two daughters and five grandchildren. Ria and her husband, Mike, who passed away in 2015, were deeply involved with the Heschel School from its earliest days. Ria is currently an Honorary Trustee.