Sam fogelman

Simcha Fogelman, also known as Sam, was born in Dokshitz (Dokshytzy), Belarus, on June 20, 1913 to Vichna (Ruderman) and Berel Fogelman (also spelled Fagelman). He had four siblings: Sara, Malka, Bella, and Leibele. His father owned a general store and his mother was a seamstress. Simcha’s father had emigrated to the United States in 1907. He encouraged his wife to join him, but her father insisted, “You cannot be Jewish in America.” So Simcha’s father returned to Dokshitz after working in New Haven, Connecticut, for five years. (While there, he helped bring over his aunt, Gitta Fagelman Kazin, the mother of American literary critics Alfred Kazin and Pearl Bell Kazin.) In the mid-1920’s Vichna’s brother, Rabbi Yaakov Yitzchak Ruderman, a Talmudic illui (prodigy), was sent to the Cleveland Yeshiva, and later founded the Ner Israel Yeshiva in Baltimore.

In 1923, when Simcha was just 10 years old, his father died, leaving his mother alone to care for the family. The following year, she sent Simcha to Vilna, which was then part of Poland, where he worked in a bakery owned by relatives. In 1930, Simcha’s oldest sister, Sara, emigrated to British-Mandate Palestine; four years later, his mother and three siblings followed her there. At the time, Simcha was conscripted into the Polish army so he couldn’t join them. When the Nazis invaded Poland, in September 1939, he fled to Ilya in Belarus, a small but thriving town with about 1000 Jews. He lived there for two years with his paternal aunt Sheyna and her husband, Hillel Kapelovitz, while working at a bakery. During this time, Ilya was under Soviet occupation resulting from a treaty with Nazi Germany.

On June 22, 1941 the Nazis broke the pact, attacking Russian forces in Eastern Europe and occupying Belarus. They swiftly implemented anti-Jewish laws and established a ghetto. On March 17, 1942, the Germans rounded up and exterminated nearly all of Ilya’s roughly 1000 Jews, among them Simcha’s aunt and uncle. They took them to a storage facility on the outskirts of town, separated those considered to be skilled workers, forced the rest to undress, gunned them down, and set the mass grave on fire.

Simcha survived because he had gone to work at the bakery early that morning, and a Christian co-worker lied when asked if any Jews were in the facility, then helped Simcha hide in the attic until the Aktion was over. He returned to the ghetto to find that his friend Feivel Solomiansky (known as Shraga Dgani after he emigrated to Israel) had also escaped the massacre. They were among around 100 Jews who were spared until the ghetto was liquidated less than two months later, on June 7.

When the Germans returned to massacre Ilya’s remaining Jews, Simcha and Shraga managed to hide in a cellar and escape into the forest. For the next five months, they slept outdoors, venturing now and then to the homes of remote farmers in search of food. As winter approached, and they grew worried about enduring the cold months without proper clothing or food, Simcha and Feivel connected with Gennady Safonov, a Soviet lieutenant who was one of the leaders of a partisan unit that operated in the Rudniki forests south of Vilna. He welcomed them into his ranks and they fought with this group of Belarusian partisans until June 1944, when they were recruited into the Red Army. Simcha served as a guard for the leader of the Red Army and was with the forces that helped end the war with the Battle of Berlin. He worked as a translator, using his knowledge of German, Yiddish, Polish, Russian, Lithuanian, and Hebrew, until he had to return to Belarus. With some goods that he managed to procure along the way, he bribed a border guard to escape back to Germany.

One day, while he was riding a tram, Simcha saw Leah Bursztyn, a young woman he had crossed paths with at an information center for survivors on his way from Belarus to Germany. When he asked her if she knew where he could find lodging, Leah suggested the DP camp where her family was living. They had survived the war by fleeing Eastward following the Nazi invasion of Poland, ultimately making their way to Kazakhstan.

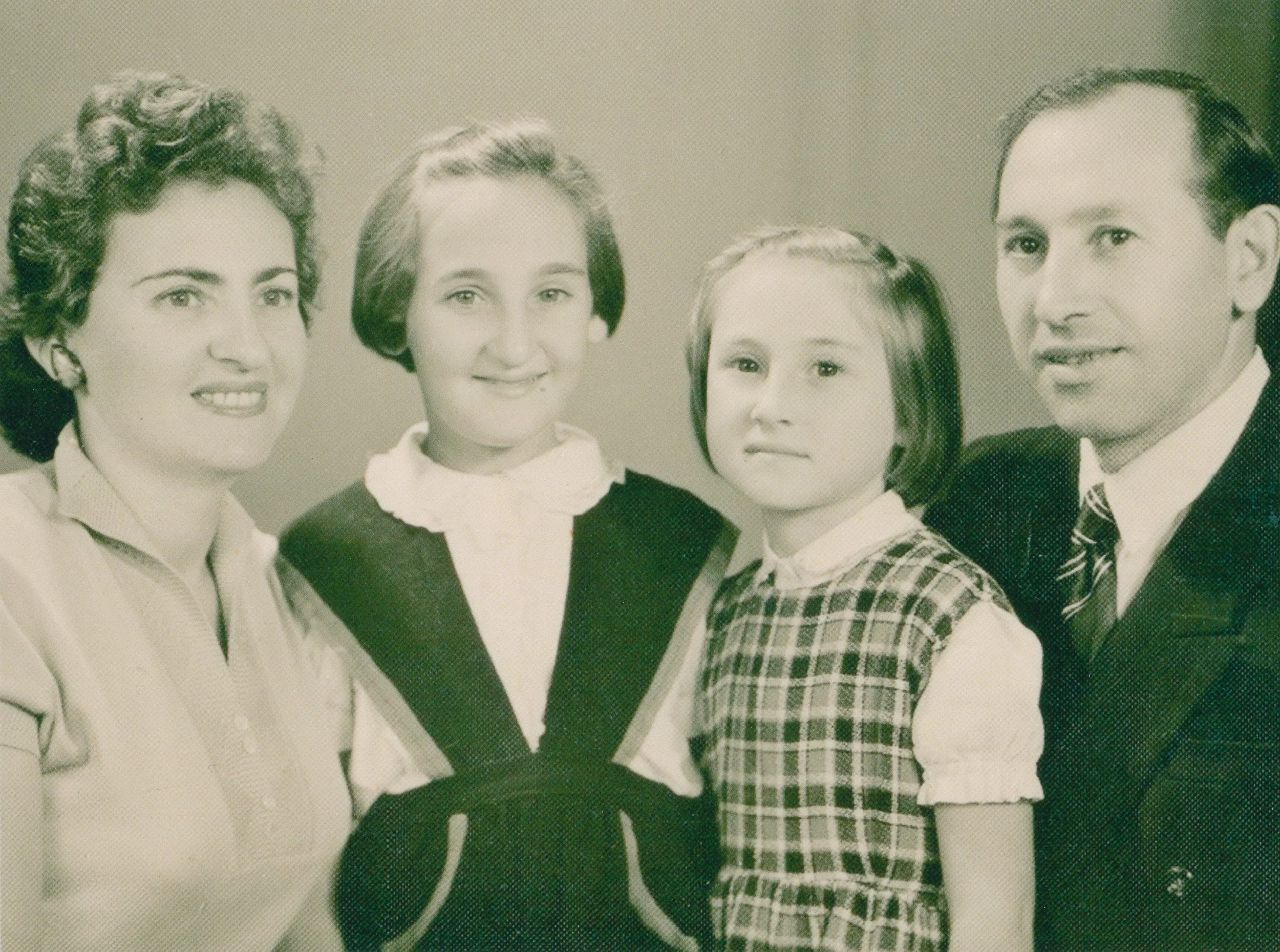

Leah and Simcha started doing business together, buying and selling whatever goods they could get their hands on, and their relationship flourished. They were married in April 1948, and their daughter Chaviva (“Eva”) was born in a half-burned-out hospital in the DP camp in 1949. In June of that year, they emigrated to the new state of Israel to reunite with Simcha’s mother and three siblings, who had emigrated to British-Mandate Palestine in 1935. His father died in 1923, when he was just 10 years old, and his younger brother, Leibele (also known as Arieh) was killed during Israel’s War of Independence, valiantly fighting in several battles to capture the strategic Latrune hilltop. Leah and Simcha had a second daughter, Gila, in 1952. In Israel, Leah took care of the home and children, while Simcha worked as a baker. He also served in the Israeli army during the 1956 Suez Crisis. The Fogelmans lived in Neve Oz, a suburb of Petach Tikva, and then in the city’s Shikun Mapam neighborhood, before moving to the United States on April 18, 1959.

The family settled in Brooklyn, first in Boro Park, and later in Sheepshead Bay. Simcha continued to make a living as a baker until Leah convinced him to buy a knitting mill. He became a mechanic for the machinery and she supervised workers at the company, which was located in Brooklyn Heights. Simcha died tragically on Hoshana Rabbah in 1999, a few days after being hit by a driver while crossing the street to buy groceries. He was 86 years old. Leah was the same age when she passed away in 2012 from an optic aneurism.

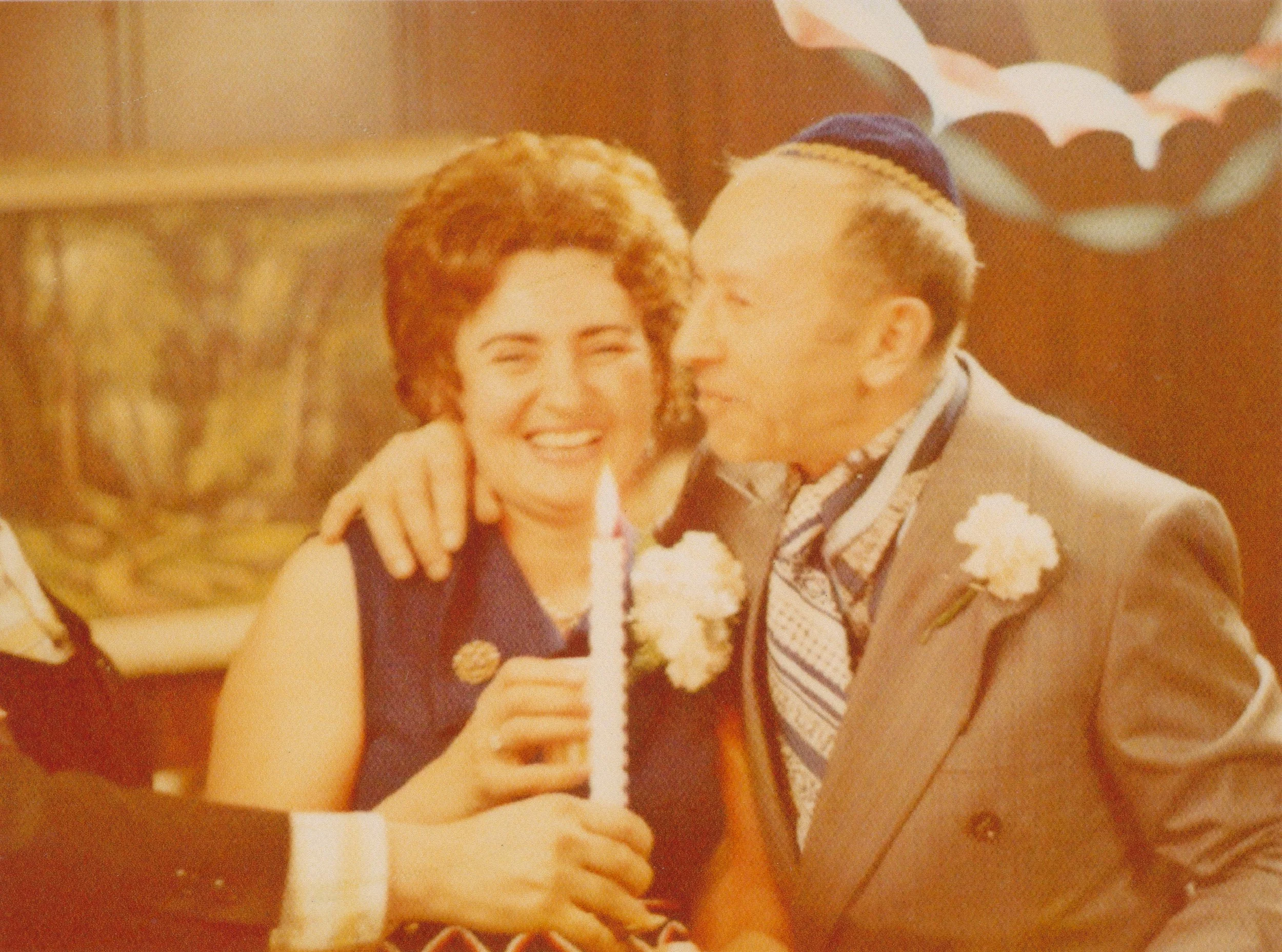

Their older daughter Eva, a longtime member of Heschel’s Holocaust Commemoration Committee, and mother of Adam Fogelman Chanes (Heschel 2014), went on to become a psychologist specializing in the effects of the Holocaust on survivors and their descendants. She is a founder of the Second-Generation movement, having helped pioneer the development of groups for children of survivors, at the Hillel of Boston University in 1976. She is also a co-founder of the Jewish Foundation for the Righteous and a founder of the Hidden Child Foundation. Dr. Fogelman has authored numerous publications, including the Pulitzer Prize-nominated 1995 book Conscience and Courage: Rescuers of Jews During the Holocaust. She also wrote and co-produced the award-winning PBS documentary Breaking the Silence: The Generation After the Holocaust. Eva is married to Jewish studies professor, author, and journalist Jerome A. Chanes,